Highlights

- Identifying and validating new broad-based therapeutic targets for treating immune-mediated diseases.

- Developing and refining improved animal models of immune-mediated diseases.

- Developing computational models of autoimmune responses to investigate pathogenesis and treatment

- Major focus of the lab in autoimmune disease is centered around IBD and type 1 diabetes.

Ongoing Efforts

Immune-mediated (or autoimmune) diseases refers to a group of diseases characterized by dysregulated immune responses leading to tissue damaging inflammation.The NIMML aims to comprehensively and systematically characterize mechanisms of immune dysregulation that contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Type-1 Diabetes, psoriasis, asthma, allergies, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Publications

Nutritional protective mechanisms against gut inflammation.

Activation of PPARγ and δ by dietary punicic acid ameliorates intestinal inflammation in mice.

Dietary conjugated linoleic acid and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in inflammatory bowel disease.

Model of colonic inflammation: immune modulatory mechanisms in inflammatory bowel disease.

Highlights

- Identifying novel naturally occurring compounds with anti-inflammatory properties for the prevention and treatment of IBD.

- Exploring the role of LANCL2 as a molecular target for anti-inflammatory nutritionals, medical foods and IBD drugs.

- Investigating the modulation of mucosal immune responses by dietary and nutritional compounds.

- Characterizing interactions between diet, microbiome and immune response that modulate IBD.

Ongoing Efforts

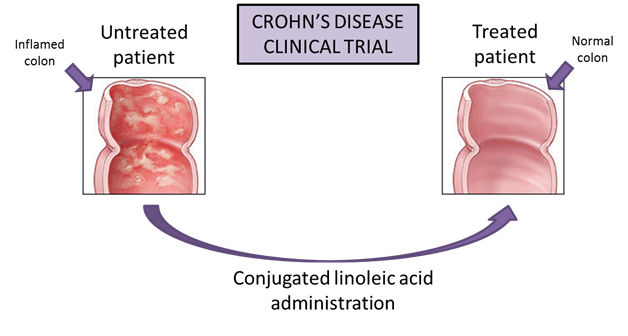

The NIMML has developed novel nutritional interventions aimed at preventing or treating IBD. In 2004, our Gastroenterology seminal article demonstrated that conjugated linoleic acid ameliorates colitis in mice through a mechanism that requires expression of PPAR g in immune and epithelial cells. The results of that study were validated in a novel pig model of IBD and a human clinical trial inhumans with Crohn’s disease.

Development of Novel Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a widespread and debilitating illness characterized by chronic inflammation in the digestive tract. It affects up to 0.5% of the human population in developed countries and numbers are increasing in the developing world. IBD primarily includes two clinical manifestations: Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), both of which can sometimes lead to painful and life-threatening complications. The main difference between UC and CD is the location and nature of inflammation. UC is characterized by the presence of chronic and localized inflammation and superficial lesions in the colonic and rectal mucosa, whereas CD is associated with discontinuous and “transmural” lesions of the gut wall which can affect the whole intestine, from mouth to anus, although the majority of the cases start in the terminal ileum. Both UC and CD patients usually go through different stages regarding the intensity and severity of the illness. The disease is considered to be in an active stage when the patients undergo a flare-up of the condition and present severe inflammation. When the inflammation is reduced or absent the disease is considered to be on remission and the patient does not present any symptom.

Cause

IBD is considered an idiopathic illness since its cause remains still unknown. Although genetic, infectious, immunologic, and psychological factors have been considered to influence the development of IBD, the most recent hypothesis suggest that IBD is the result of a body failure to turn off normal immune responses. The gastrointestinal tract becomes inflammed when the immune system tries to fight an invading microorganism or virus. An autoimmune reaction in which the body mounts an immune response towards normal microflora can also result in inflammation that continues without control and can lead to abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea.

Symptoms

IBD symptoms may vary depending on the severity and location of inflammation, ranging from mild to severe and including the following:

- Abdominal pain and cramping

- Severe and bloody diarrhea

- Fever

- Malnutrition or weight loss

- Anemia (as a result of blood loss)

In more severe cases of IBD, especially in Crohn’s disease patients, inflammation can result in intestinal complications including the following:

- Ulceration and bleeding

- Perforation of the bowel

- Strictures and obstruction

- Fistulae and perianal disease

- Toxic megacolon (acute dilatation of the colon)

- Inflammation-induced colorectal cancer

Treatment

The aim of IBD treatment is to reduce the inflammation that leads to the mentioned symptoms. The ultimate goal is not only to relief the symptoms but to achieve a long-term remission of the patient. Current treatments for CD include:

- Corticosteroids (i.e., prednisone and budesonide)

- Antibiotics

- Immunomodulators (i.e., azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, and methotrexate)

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha antibody (Infliximab; Remicade®)

Despite evidence that CD therapies have improved, they are modestly successful for the long-term management of the disease and result in significant side effects such as immune suppression, enhanced susceptibility to malignancies, and suppressed resistance against infectious diseases. Moreover, two-thirds to three-quarters of patients with Crohn’s disease will require surgery at some point during their lives, which becomes necessary in Crohn’s disease when medications can no longer control the symptoms. Therefore, there is a need to identify novel and safer therapies for the treatment of IBD. In this regard, and consistent with the concept from bench to bedside, our group has translated the basic scientific understanding of cellular and molecular processes to the clinic through collaborations with Wake Forest University and the Digestive Health Center of Excellence at the University of Virginia. Under a contract from Cognis (now BASF) awarded to the NIMML, we have investigated the ability of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) to down-regulate intestinal inflammation and ameliorate gut health and we have discovered important new information on the efficacy of CLA in treating patients with CD.

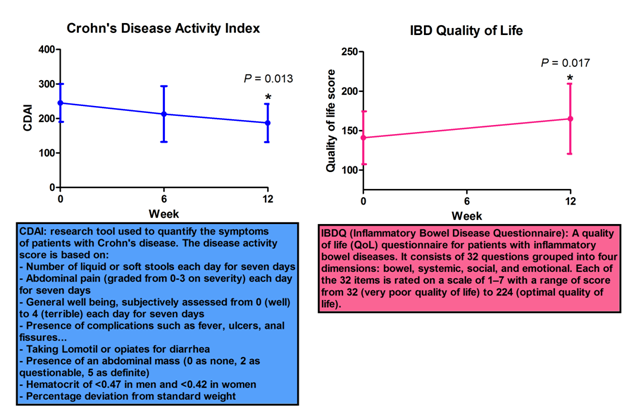

The clinical trial, which was managed as an Investigational New Drug (IND) trial, found that CD patients who took supplementary CLA showed noticeable improvement. CLA was administered as a supplement (6 g/day orally) in thirteen study subjects with mild to moderate CD for 12 weeks and we found a marked improvement in disease activity and quality of life, and importantly, no adverse side effects since CLA was well tolerated by all of the study subjects. Specifically, there was a statistically significant drop in Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) from 245 to 187 (P = 0.013) and increase in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ) regarding quality of life from 141 to 165 (P = 0.017) on week 12. Moreover, CLA significantly suppressed the ability of peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines including IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-17 and to proliferate at week 12. In summary, CLA represents a promising new supportive intervention for gut inflammation. This is in contrast with the results of human clinical studies using n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in IBD that remain largely unimpressive. The present study has shed new light on the clinical potential of this compound and provided insights on the possible mechanisms of immune modulation targeted by CLA in the human system. Based on these results, a larger Phase II double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial with several doses of CLA is warranted.

Collaborators

- Richard Bloomfeld (Digestive Health Center; Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center)

- Stephen J. Bickston (Digestive Health Center of Excellence; VCU Medical Center)

- Kim Isaacs (Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, UNC Department of Medicine)

- Hans Herfarth (Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, UNC Department of Medicine)

- Paul Yeaton (Division of Gastroenterology, Carilion School of Medicine)

- Dario Sorrentino (Carilion School of Medicine)

Publications

- Bassaganya-Riera, J., R. Hontecillas, W. T. Horne, M. Sandridge, H. H. Herfarth, R. Bloomfeld, K. L. Isaacs (2012) Conjugated linoleic acid modulates immune responses in patients with mild to moderately active Crohn’s disease. Clinical Nutrition. 5: 721-727. [ PubMED ]

- Bassaganya-Riera, J. and R. Hontecillas (2010) Dietary conjugated linoleic acid and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 2010. 13: p. 569-573. [ PubMED ]

- Hontecillas, R and J. Bassaganya-Riera (2007) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma is required for regulatory CD4+ T cell-mediated protection against colitis. J. Immunol. 178: 2940-2949. [ PubMED ]

- Bassaganya-Riera, J., and R. Hontecillas (2006) CLA and n-3 PUFA differentially modulate clinical activity and colonic PPAR-responsive gene expression in a pig model of experimental IBD. Clinical Nutrition. 25: 454-65 [ PubMED ]

- Hontecillas, R., J. Bassaganya-Riera, J. Wilson, D. Hutto, and M. J. Wannemuehler (2005) CD4+ T cell responses and distribution at the colonic mucosa during Brachyspira hyodysenteriae-induced colitis in pigs. Immunology. 115: 127-135. [ PubMED ]

- Bassaganya-Riera, J., K. Reynolds, S. Martino-Catt, Y. Cui, L. Hennighausen, F. Gonzalez, J. Rohrer, A. Uribe Benninghoff, and R. Hontecillas (2004) Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and delta by conjugated linoleic acid mediates protection from experimental inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 127: 777-791. [ PubMED ]

- Hontecillas, R., J.Bassaganya-Riera (2003) Differential requirements for proliferation of CD4+ and gammadelta+ T cells to spirochetal antigens. Cellular Immunol. 224: 38-46. [ PubMED ]

- R. Hontecillas, D.L. Hutto, D. U. Ahn, J. H. Wilson, M. J. Wannemuehler, and J. Bassaganya-Riera. (2002) Nutritional regulation of bacterial-induced colitis by dietary conjugated linoleic acid. J. Nutr. 132: 2019-2027. [ PubMED ]

- Bassaganya-Riera, J., R. Hontecillas, D.C. Beitz. (2002) Colonic Anti-inflammatory Mechanisms of Conjugated Linoleic Acid. Clinical Nutrition 21 (6): 451-459. [ PubMED ]

Figure 1. Crohn's Disease Clinical Trial

Figure 1. Crohn's Disease Clinical Trial

Figure 2. CLA IBD

Figure 2. CLA IBD